WALNUT CREEK, CA—Diatoms, mighty microscopic algae, have profound influence on climate, producing 20 percent of the oxygen we breathe by capturing atmospheric carbon and in so doing, countering the greenhouse effect. Since their evolutionary origins these photosynthetic wonders have come to acquire advantageous genes from bacterial, animal and plant ancestors enabling them to thrive in today’s oceans. These findings, based on the analysis of the latest sequenced diatom genome, Phaeodactylum tricornutum, are published in 15 October edition of the journal Nature by an international team of researchers led by the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (DOE JGI) and the Ecole Normale Supérieure of Paris.

The researchers compared Phaeodactylum with the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana, previously sequenced by DOE JGI, revealing a wealth of information about diatom biology, particularly the rapid diversification among the hundreds of thousands of diatom species that exist today. Phaeodactylum was targeted for sequencing due to its value as a diatom model, given the ease with which it can be grown in the lab and the availability of tools to genetically transform it, and the comparisons with the previously sequenced diatom genome of Thalassiosira pseudonana.

“These organisms represent a veritable melting pot of traits—a hybrid of genetic mechanisms contributed by ancestral lineages of plants, animals, and bacteria, and optimized over the relatively short evolutionary timeframe of 180 million years since they first appeared,” says first author Chris Bowler of the Ecole Normale Supérieure. “Our findings show that gene transfer between diatoms and other organisms has been extremely common, making diatoms ‘transgenic by nature’,” he adds.

The wholesale acquisition of genetic material has provided food for thought to researchers bent on characterizing the diatom’s staying power and ability to cope with environmental change.

“We believe this is the first time bacterial horizontal gene transfer has been observed in eukaryotes at such scale,” says senior author Igor Grigoriev of DOE JGI. “This study gets us closer to explaining the dramatic diversity across the genera of diatoms, morphologically, behaviorally, but we still haven’t yet explained all the differences conferred by the genes contributed by the other taxa.”

From plants, the diatom inherited photosynthesis, and from animals the production of urea. Bowler speculates that the diatom uses urea to store nitrogen, not to eliminate it like animals do, because nitrogen is a precious nutrient in the ocean. What’s more, the tiny alga draws the best of both worlds—it can convert fat into sugar, as well as sugar into fat—extremely useful in times of nutrient shortage.

The team documented more than 300 genes sourced from bacteria and found in both types of diatoms, pointing to their ancient origin and suggesting novel mechanisms of managing nutrients—for example utilization of organic carbon and nitrogen—and detecting cues from their environment.

Diatoms, encapsulated by elaborate lacework-like shells made of glass, are only about one-third of a strand of hair in diameter. “The diatom genomes will help us to understand how they can make these structures at ambient temperatures and pressures, something that humans are not able to do. If we can learn how they do it, we could open up all kinds of new nanotechnologies, like for building miniature silicon chips or for biomedical applications,” says Bowler.

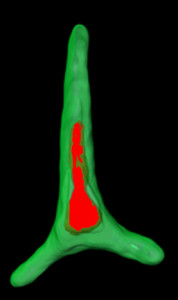

Diatoms reside in fresh or salt water and can be divided into two camps, centrics and pennates. The centric Thalassiosira resemble a round “Camembert” cheese box (only much smaller) and pennates like Phaeodactylum look more like a cross between a boomerang and a narrow three-cornered hat—hence the species name, tricornutum. Not only is their shape and habitat diverse, so too is their behavior; for instance, the former get around by floating, the latter by gliding through the water or on surfaces.

The lifestyle of diatoms can be characterized as “bloom or bust.” When light and nutrient conditions in the upper reaches of the ocean are favorable, particularly at the onset of spring, diatoms gain an edge and tend to dominate their phytoplankton brethren. When food is scarce, they die and sink, carrying their complement of carbon dioxide to the deeper recesses.

Bowler and his colleagues are also trying to understand the role that iron plays in the Phaeodactylum’s development. Iron is even more precious than nitrogen in the ocean and its absence in the southern hemisphere is likely a major cause of oceanic deserts of photosynthesis there. Bowler’s team has demonstrated that when iron deficiency occurs processes such as photosynthesis and nitrogen assimilation are suppressed. Other studies, which hail diatoms as champions in capturing carbon dioxide, suggest a bold strategy of using iron as a fertilizer to provoke massive diatom blooms. “Once they have feasted, the weight of their silicon shells, which resemble glass, causes the diatoms to sink to the bottom of the ocean when they die, and the carbon that they assimilated is trapped there for millennia,” says Bowler. “By sequestering carbon in this way we could reverse the damage from the burning of fossil fuels.”

Other DOE JGI authors on the Nature study include Alan Kuo, Robert Otillar, Asaf Salamov, Chris Detter, Erika Lindquist, Susan Lucas, Harris Shapiro, Daniel Rokhsar, and Igor Grigoriev as well as Jane Grimwood and Jeremy Schmutz of JGI at the HudsonAlpha Institute.

The U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute, supported by the DOE Office of Science, unites the expertise of five national laboratories — Lawrence Berkeley, Lawrence Livermore, Los Alamos, Oak Ridge, and Pacific Northwest — along with the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology — to advance genomics in support of the DOE missions related to clean energy generation and environmental characterization and cleanup. DOE JGI’s Walnut Creek, CA, Production Genomics Facility provides integrated high-throughput sequencing and computational analysis that enable systems-based scientific approaches to these challenges.