In the Lewis Carroll classic, Through the Looking Glass, Humpty Dumpty states, “When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.” In turn, Alice (of Wonderland fame) says, “The question is, whether you can make words mean so many different things.” All organisms on Earth use a genetic code, which is the language in which the building plans for proteins are specified in their DNA. It has long been assumed that there is only one such “canonical” code, so each word means the same thing to every organism. While a few examples of organisms deviating from this canonical code had been serendipitously discovered before, these were widely thought of as very rare evolutionary oddities, absent from most places on Earth and representing a tiny fraction of species. Now, this paradigm has been challenged by the discovery of large numbers of exceptions from the canonical genetic code, published by a team of researchers from the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (DOE JGI) in the May 23, 2014 edition of the journal Science.

“What we saw in the study was that in certain organisms, the stop sign was not interpreted as stop.” – Eddy Rubin. (Illustration by Wayne Keefe, Berkeley Lab Creative Services)

“All along, we presumed that the code or vocabulary used by organisms was universal, applying to all branches of the tree of life, with vanishingly few exceptions,” said DOE JGI Director Eddy Rubin, and senior author on the Science paper. “We have now confirmed that this just isn’t so. There is a significant portion of life that uses different vocabularies where the same word means different things in different organisms.”

This research was conducted under the DOE JGI’s continuing effort to explore the biological frontier known as “microbial dark matter.” These are the vast number of microbes that are difficult-to-impossible to grow and study in the laboratory but populate nearly all environments from the human gut to the hot vents at the bottom of the ocean. Approximately 99% of all microbial species on Earth fall in this category, defying culture in the laboratory but profoundly influencing the most significant environmental processes from plant growth and health, to the carbon and other nutrient cycles on land and sea, and even climate processes.

“The tools of metagenomics and single-cell genomics, with which we determine the genetic blueprints of microbes without the need to grow them in the laboratory, provide us a window into the unexplored, uncultured microbial world,” Rubin said. “The metaphor we use is that up until very recently we have just been looking under the lamppost for new life, studying organisms that we can grow in the laboratory while we know most microbial life is very resistant to being grown in the lab. In this project, using metagenomics and single-cell genomics to explore uncultured microbes, we really had the opportunity to see how the genetic code operates in the wild. It is helping us get an unbiased view of how nature operates and how microbes manage our planet.”

It has been 60 years since the discovery of the structure of DNA and the emergence of the central dogma of molecular biology, wherein DNA serves as a template for RNA and these nucleotides form triplets of letters called codons. There are 64 codons, and all but three of these triplets encode actual amino acids—the building blocks of protein. The remaining three are “stop codons,” that bring the molecular machinery to a halt, terminating the translation of RNA into protein. Each has a given name: Amber, Opal and Ochre. When an organism’s machinery reads the instructions in the DNA, builds a protein composed of amino acids, and reaches Amber, Opal or Ochre, this triplet would signal that they have arrived at the end of a protein.

“This is sort of a ‘stop sign,’” Rubin said. “But what we saw in the study was that in certain organisms, the stop sign was not interpreted as stop, rather it signaled to continue adding amino acids and expand the protein.”

The particular observation that caught the team’s interest in looking for breakdowns in the canonical genetic code was when the study’s lead investigator, DOE JGI’s Natalia Ivanova, came across an anomaly: bacteria with extraordinarily short genes of only 200 base pairs in length. Typically, genes from microbes are about 800-900 base pairs long.

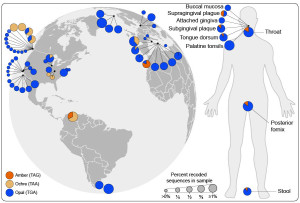

Captured in this map are the recoded DNA sequences identified worldwide showing the locations of 82 environmental samples around the globe together with nine sample sites (derived from 212 samples) of the human body for which recoded sequences have been identified. (Figure by Patrick Schwientek)

“When trying to interpret the sequence of these bacteria using the canonical codon table, Opal, normally interpreted as a stop sign, resulted in the bacteria having unbelievably short genes. When Natalia applied a different vocabulary where Opal, instead of be interpreted as a stop, was assumed to encode the amino acid glycine, the genes in the bacteria suddenly appeared to be of normal length,” Rubin said. Their interpretation of the finding was that “Opal-recoded” organisms, instead of stopping, incorporated an amino acid into the polypeptide, which kept growing and eventually produced normal-sized proteins.

Following this finding they wanted to see how frequently this occurs in nature and looked for similar occurrences in enormous amounts of sequence data from uncultured microbes. Computationally they sifted through a massive “haystack” of sequence data, 5.6 trillion letters of genetic code (the equivalent of nearly 2,000 human genomes). These came from over 1,700 samples sourced from far-flung and esoteric locations that span the globe—marine, fresh water, and terrestrial environments—to those much closer to home and more prosaic—from the human mouth and gut.

“We were surprised to find that an unprecedented number of bacteria in the wild possess these codon reassignments, from “stop” to amino-acid encoding “sense,” up to 10 percent of the time in some environments,” said Rubin.

Workflow (depicted in the amount of DNA sequence data generated in trillion of nucleotide bases [Tb] and billion bases [Gb]) to identify the set of overlapping DNA segments that contain stop codon (Amber, Ochre, Opal) reassignments. (Figure by Patrick Schwientek)

“To make this all happen, the established dogma was that phage needed to employ the exact genetic code that the host cell uses, otherwise, whatever DNA they inject wouldn’t be properly translated,” Rubin said. “But we observed phage with codon vocabularies that did not match any we found in their bacterial hosts. We scratched our heads at this result, because we wondered about what was up with the host. The dogma tells us that the phage need to share the same code as the host, but we saw no Amber in bacteria. So what were these phage doing?”

The punch line, Rubin said, is that the dogma is wrong.

“Phage apparently don’t really ‘care’ about the codon usage of the host. They have ways to get around that, and in fact they use differences to attack the host.” The phage use certain molecular tricks, just those slight changes in the codon table, to suppress the host cell’s protective mechanisms to conduct a ‘hostile takeover’ of the cell. “We call this strategy ‘codon warfare’,” Rubin said. “We need to keep this in mind when characterizing environments and how their resident microbes contribute to biochemical and biogeochemical processes. Now that our assumptions about the canonical nature of the codon table are shaken up, we will be able to devise new analysis methods that take this phenomenon of unexpected complexity into consideration so we can obtain a better understanding of how these environments function.”

Additional food for thought, Rubin noted, is whether adequate controls can effectively be established for those emergent organisms developed through synthetic biology. Some of these organisms have been engineered with an intentionally altered genetic code, designed as a “firewall” to prevent the exchange of genetic information between laboratory-engineered microbes and their cousins in the wild.

Alice in Wonderland certainly captured the vexations of nature’s complexity: “If I had a world of my own, everything would be nonsense.”

Watch a presentation on this topic by DOE Joint Genome Institute Director Eddy Rubin at the recent DOE JGI Genomics of Energy & Environment Meeting: http://bit.ly/JGIUM9Rubin.