Collaborative science initiative enables resolution of fungal protein complexes.

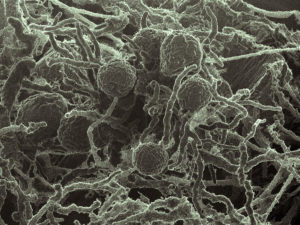

Scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of Neocallimastix californiae, a representative of the Neocallimastigomycetes, a clade of the early-diverging fungal lineages that are not well-studied. It’s one of three Neocallimastigomycetes sequenced and annotated by the DOE JGI for this study. (Chuck Smallwood, PNNL)

One of the biggest barriers in the commercial production of sustainable biofuels is to cost-effectively break down the bioenergy crops into sugars that can then be converted into fuel. To reduce this barrier, bioenergy researchers are looking to nature and the estimated 1.5 million species of fungi that, collectively, can break down almost any substance on earth, including plant biomass.

As reported May 26, 2017 in Nature Microbiology, a team led by researchers at the University of California (UC), Santa Barbara has found for the first time that early lineages of fungi can form complexes of enzymes capable of degrading plant biomass. By consolidating these enzymes, in effect into protein assembly lines, they can team up to work more efficiently than they would as individuals. The work was enabled by harnessing the capabilities of two U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facilities: the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI) at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab); and, the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory (EMSL) at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL).

“There are protein complexes in bacteria called cellulosomes that pack together the enzymes to break down plant biomass,” said study senior author Michelle O’Malley of UC Santa Barbara. “The idea is that these clusters are better at attacking biomass because they are keeping the different enzymes in place with plugs called dockerins so they work more efficiently. This has been detailed in bacteria for more than 20 years, but now seen for the first time in fungi.”

Omics Lend Insights to Fungal Enzyme Complexes

With help from both the DOE JGI and EMSL, the team has now found protein complexes in anaerobic gut fungi that O’Malley said in principle do the same thing—attack plant biomass as a cluster of enzymes. While they found that many of enzymes in these complexes resulted from horizontal gene transfers with gut bacteria, they also noted differences in the composition compared to the bacterial cellulosomes. For one thing, both dockerins and scaffoldin are not similar between fungi and bacteria. Also, the bacterial cellulosomes are species-specific. Think of them as the high school clique that does everything together. In contrast, the fungal structures that appear analogous to the bacterial cellulosomes are like the high school kids who could easily move among various social groups and are comprised of clusters of enzymes that can “dock” and work in other fungi.

The study involved a comparative genomics analyses of five fungi that belong to the Neocallimastigomycetes, a clade of the early-diverging lineages that are not well-studied. Three of the fungi were isolated from animal gut samples collected by the UC Santa Barbara team and sequenced and annotated by the DOE JGI. “Proteomics data and genomics data enabled us to figure out what these complexes are and go hunting for them in other genomes,” O’Malley said. “The three genomes are really well resolved to the point where you can start looking at what’s there, what’s regulating enzyme production, and how enzymes have evolved.”

Study co-senior author and DOE JGI Fungal Genomics Program head Igor Grigoriev noted that a multi-omics approach that harnessed the genomics and molecular characterization capabilities through a collaborative science initiative allowing researchers to access multiple user facilities in one proposed project known as Facilities Integrating Collaborations for User Science (FICUS), was critical for the research.

“It’s the first time we’ve seen parts of the fungal cellulosome,” Grigoriev said. “Through the JGI-EMSL FICUS initiative, proteomics allowed us to find the first of these really large ~700 kiloDaltons (kDa) fungal proteins that hold all enzymes together (compared to the molecular weight of 34 kDa of an average protein). Then the high quality of genome assemblies enabled identification of multiple copies of this protein in each of the gut fungi genomes. Just having proteomics or sequencing tools isn’t enough since these proteins are not similar to anything else outside of Neocallimastigomycetes. Though the fungal cellulosome was discovered through proteomics, we needed genomics and transcriptomics to decode all its parts.”

Digging Deeper with High-Resolution Genomes

UC Santa Barbara researcher Michelle O’Malley and her lab led the work published in Nature Microbiology. (Courtesy of Michelle O’Malley)

The work is an extension of O’Malley’s studies of anaerobic gut fungi, which appeared in Science last year (watch her talk from the 2016 DOE JGI Genomics of Energy & Environment Meeting at bit.ly/JGI2016OMalley). It’s a lot of the same players, but we’re digging deeper now because we have high-resolution genomes, and we didn’t have them then,” she said. “We’re able to conduct more comparative genetics and now we’re trying to figure out the ecological roles in their microbiome.”

Understanding in greater detail the protein mechanisms of biomass degradation is crucial to advancing DOE’s agenda to develop sustainable biofuels from plant feedstocks. High throughput sequencing, combined with sophisticated proteomics, illuminates not just the diversity and complexity of fungal biomass degradation capacities but also furnishes a knowledge basis for exploitation of these abilities with synthetic biology and metabolic engineering approaches.

Support for this work was provided by the DOE Office of Science, including an Early Career Research Program award, as well as the National Science Foundation, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the U.S. Army Research Office, and the University of California.

***

EMSL, the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, is a DOE Office of Science User Facility. Located at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland, Wash., EMSL offers an open, collaborative environment for scientific discovery to researchers around the world. Its integrated computational and experimental resources enable researchers to realize important scientific insights and create new technologies. Follow EMSL on Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter.

Interdisciplinary teams at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory address many of America’s most pressing issues in energy, the environment and national security through advances in basic and applied science. Founded in 1965, PNNL employs 4,400 staff and has an annual budget of nearly $1 billion. It is managed by Battelle for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. As the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, the Office of Science is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information on PNNL, visit the PNNL News Center, or follow PNNL on Facebook, Google+, LinkedIn and Twitter.