Photo: There are more microbes in, on and around the Earth than there are stars in the sky, and we only know about a small fraction of the microbial diversity around us. In an effort to learn more about the “microbial dark matter,” researchers are sequencing and analyzing samples collected from around the world. (Composition by Zosia Rostomian, Berkeley Lab)

Is space really the final frontier, or are the greatest mysteries closer to home? In cosmology, dark matter is said to account for the majority of mass in the universe, however its presence is inferred by indirect effects rather than detected through telescopes. The biological equivalent is “microbial dark matter,” that pervasive yet practically invisible infrastructure of life on the planet, which can have profound influences on the most significant environmental processes from plant growth and health, to nutrient cycles in terrestrial and marine environments, the global carbon cycle, and possibly even climate processes. By employing next generation DNA sequencing of genomes isolated from single cells, great strides are being made in the monumental task of systematically bringing to light and filling in uncharted branches in the bacterial and archaeal tree of life. In an international collaboration led by the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (DOE JGI), the most recent findings from exploring microbial dark matter were published online July 14, 2013 in the journal Nature.

“Instead of wondering through the starkness of space, this achievement is more like the 21st Century equivalent of Lewis and Clark’s expedition to open the American West,” said Eddy Rubin, DOE JGI Director. “This is a powerful example of how the DOE JGI pioneers discovery, in that we can take a high throughput approach to isolating and characterizing single genomes from complex environmental samples of millions of cells, to provide a profound leap of understanding the microbial evolution on our planet. This is really the next great frontier.”

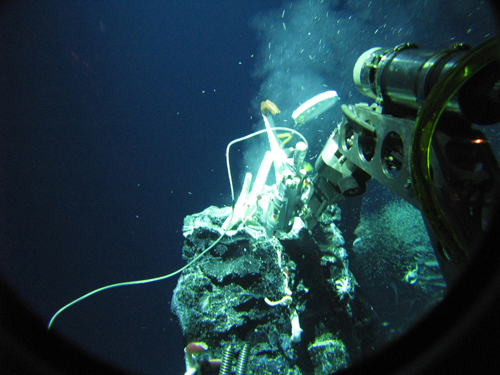

This microbial dark matter campaign targeted uncultivated microbial cells from nine diverse habitats: Sakinaw Lake in British Columbia; the Etoliko Lagoon of western Greece; a sludge reactor in Mexico; the Gulf of Maine; off the north coast of Oahu, Hawaii, the Tropical Gyre in the south Atlantic; the East Pacific Rise; the Homestake Mine in South Dakota; and the Great Boiling Spring in Nevada. From these samples, the team laser-sorted 9,000 cells, from which they were able to reassemble and identify 201 distinct genomes, which then could be aligned to 28 major previously uncharted branches of the tree of life.

Photo: Crab Spa is a diffuse-flow hydrothermal vent site on the East Pacific Rise and one of the nine sampling sites for this study. (Photo courtesy of Stefan Sievert, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

“Microbes are the most abundant and diverse forms of life on Earth,” said Tanja Woyke, DOE JGI Microbial Program Head and senior author on the Nature publication. “They occupy every conceivable environmental niche from the extreme depths of the oceans to the driest of deserts. However, our knowledge about their habits and potential benefits has been hindered by the fact that the vast majority of these have not yet been cultivated in the laboratory. So we have only recently become aware of their roles in various ecosystems through cultivation-independent methods, such as metagenomics and single-cell genomics. What we are now discovering are unexpected metabolic features that extend our understanding of biology and challenge established boundaries between the domains of life.”

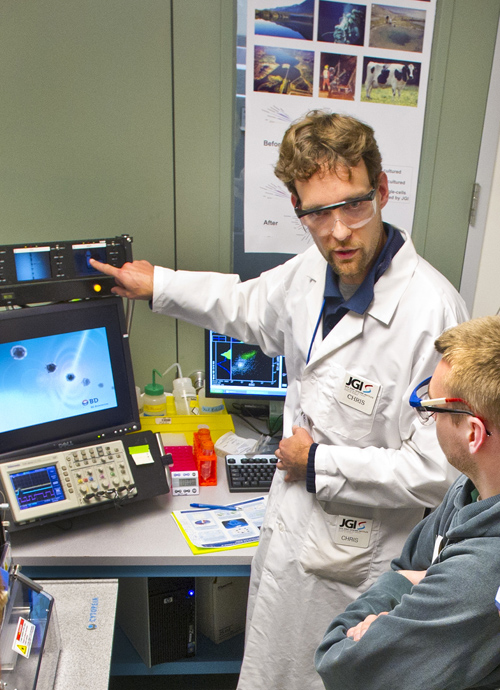

To get around the difficulty of growing most microbes in the lab, recent efforts have focused on conducting surveys based on sequencing marker or 16S ribosomal RNA genes that are conserved across microbial lineages because of their essential role as “housekeeping” genes—critical for the organism’s survival. Genome sequencing of the rest of the genomes of most of these lineages is however proceeding much more slowly. “Microbial genome representation in the databases is quite skewed,” said Chris Rinke, DOE JGI postdoctoral fellow and first author of the study. “More than three-quarters of all sequenced genomes fall into three taxonomic groups or phyla but there are over 60 phyla we know of.” For the majority of them, however, there are no cultivated members available.

“Based on 16S surveys we know they’re out there, but we don’t know much about them—that’s why we call them microbial dark matter,” Woyke added. “Using modern single-cell techniques allowed us to access the genetic make-up for some of them, even without growing them in the lab.”

In this effort to “seek out new life,” the team’s findings fell into three main areas. The first was the discovery of unexpected metabolic features. They observed certain traits in Archaea that previously only were seen in Bacteria and vice-versa. One such trait involves an enzyme that bacteria commonly use for creating space within their protective cell wall, which is needed so the cell can, for example, expand during cell division. As it rather generically cleaves the protective bacterial cell envelope, it needs to be very tightly regulated. For the first time, a group of Archaea was found to encode this potent enzyme and the authors hypothesize that Archaea may deploy it as a defense mechanism against attacking Bacteria.

Photo: Study first author Chris Rinke shows off the DOE JGI’s single-cell genomics capabilities during the annual Genomics of Energy & Environment Meeting. (Roy Kaltschmidt, Berkeley Lab)

The second contribution arising from the work was the correct reassignment, or binning, of data of some 340 million DNA fragments from other habitats to the proper lineage. This course correction provides insights into how organisms function in the context of a particular ecosystem as well as a much improved and more accurate understanding of the associations of newly discovered genes with resident life forms.

The third finding was the resolution of relationships within and between microbial phyla—the taxonomic ranking between domain and class—which led the team to propose two new superphyla, which are highly stable associations between phyla. The 201 genomes provided solid reference points, anchors for phylogeny—the lineage history of organisms as they change over time. “Our single-cell genomes gave us a glimpse into the evolutionary relationships between uncultivated organisms – insights that extend beyond the single locus resolution of the 16S rRNA tree and are essential for studying bacterial and archaeal diversity and evolution,” Woyke said. “It’s a bit like looking at a family tree to figure out who your sisters and brothers are. Here we did this for groups of organisms for which we solely have fragments of genetic information. We interpreted millions of these bits of genetic information like distant stars in the night sky, trying to align them into recognizable constellations. At first, we didn’t know what they should look like, but we could estimate their relationship to each other, not spatially, but over evolutionary time.” Woyke and her colleagues are pursuing a more accurate characterization of these relationships so that they can better predict metabolic properties and other useful traits that can be expressed by different groups of microbes.

Phil Hugenholtz, Director of the Australian Centre for Ecogenomics at The University of Queensland, a former DOE JGI researcher, and another one of the paper’s authors reinforced the motivation for taking on this expedition of sorts. “For almost 20 years now we have been astonished by how little there is known about massive regions of the tree of life. This project is the first systematic effort to address this enormous knowledge gap. One of the most significant contributions is that based on these data, we provided names for many of these lineages which, like most star systems, were just numbered previously. For me, taxonomic assignment is important as it welcomes in strangers and makes them part of the family. Yet this is just a start. We are talking about probably millions of microbial species that remain to be described,” Hugenholtz said.

Cosmologists have only mapped half of one percent of the observable universe and the path ahead in environmental genomics is similarly daunting. “There is still a staggering amount of diversity to explore,” Woyke said. “To try to capture 50 percent of just the currently known phylogenetic diversity, we would have to sequence 20,000 more genomes, and these would have to be selected based on being members of underrepresented branches on the tree. And, to be sure, these are only what are known to exist.”

The Nature publication “Insights into the phylogeny and coding potential of microbial dark matter” builds upon a DOE JGI pilot project, the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea (GEBA: and closely articulates with other international efforts such as the Microbial Earth Project which aims to generate a comprehensive genome catalog of all archaeal and bacterial type strains (http://www.microbial-earth.org), and the Earth Microbiome Project (http://www.earthmicrobiome.org). More information about GEBA-MDM is available at http://genome.jgi.doe.gov/MDM/.

Joining the DOE JGI in authorship on the MDM paper are researchers from Bielefeld University, Germany, the University of California, Davis, the University of Technology Sydney, the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, University of British Columbia, the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, the University of Western Greece, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and the Australian Centre for Ecogenomics of the University of Queensland, Australia.

Publication:

Rinke C et al. Insights into the phylogeny and coding potential of microbial dark matter. Nature. 499, 431–437 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12352

Relevant Links:

- University of Illinois news release: http://engineering.illinois.edu/news/2013/07/25/genome-sequencing-work-illuminates-microbial-dark-matter

Byline: David Gilbert