A collaborative team led by Joey Spatafora at Oregon State University, Jason Stajich at the University of California, Riverside and Igor Grigoriev from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Joint Genome Institute (JGI), a DOE Office of Science User Facility, found that the fungus Olpidium is a link in the evolution and transition of fungi from aquatic to terrestrial habitats. The work is part of the JGI’s 1000 Fungal Genomes Project, which aims to provide genomic information for every family of fungi. In the following guest piece, JGI user Ying Chang in the Spatafora lab describes the effort that led to the work published in Scientific Reports.

Before 2006, Olpidium was one of the many obscure fungi of Chytridiomycota (the “chytrids”). Most of the attention on Olpidium was from agricultural research. Several species of Olpidium are obligate endoparasites of some common crops, such as lettuce and tobacco. Olpidium itself doesn’t cause much damage to the hosts, but they are carriers of several viruses (e.g., Lettuce big-vein associated virus LBVaV; genus Varicosavirus) which may severely reduce crop yields. Like the typical chytrids and other early-diverging fungi, Olpidium reproduces by zoospores that possess a posterior flagellum, a feature demonstrating the common ancestry between fungi and animals.

Olpidium attracted the attention of many mycologists with the two publications of the kingdom-wide, multi-gene phylogeny of fungi by James et al. and Sekimoto et al. In both studies, however, Olpidium was unexpectedly grouped with non-flagellated terrestrial fungi, but not with the flagellated chytrids. This result has substantial implications on the inference of the evolution of early terrestrial fungi. Flagellum loss is believed to be closely associated with the invasion of land by fungi. It had been widely accepted that flagellum loss happened once during the terrestrialization of fungi. The placement of flagellated zoosporic Olpidium within the non-flagellated terrestrial fungi suggested that there were multiple flagellum loss events during the diversification of terrestrial fungi, given that the intricate flagellar apparatus is highly unlikely to regain once it is lost. Depending on the exact phylogenetic placement of Olpidium, it may mean that the flagellum was retained in some terrestrial fungal lineages for an extended period of time, which would be rather intriguing given the lack of selective pressure on retaining the flagellum in the terrestrial ecosystems. Unfortunately, neither paper was able to resolve the latter question, despite of their well-designed sampling and analysis of their data at the time.

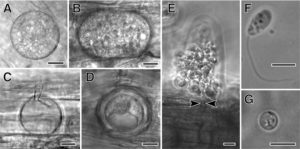

From Sekimoto et al., 2011: Olpidium bornovanus, a unicellular fungus, is an obligate parasite of plants that reproduces with flagellated, swimming zoospores. A-B. Vegetative unicellular thalli in cucumber root cells. Thalli differentiate into sporangia with zoospores, or into resting spores. C. An empty sporangium, after zoospore release. D. A thick-walled resting spore. E. Zoospores being released from a sporangium, showing the sporangium exit tube (arrowheads). F. A swimming zoospore with a single posterior flagellum. G. An encysted zoospore. Bars: A-E = 10 μm; F,G = 5 μm. (Figures are from Sekimoto et. al., 2011 used under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 License.)

Following the publication of their paper in 2011, Dr. Sekimoto from University of British Columbia and Dr. Rochon from Agri-Food Canada at Summerland BC aimed to generate whole genome data of Olpidium. This required an enormous amount of effort in collecting genetic material of Olpidium. They inoculated cucumber roots with zoospores of Olpidium bornovanus and allowed the fungus to develop within the host root. Upon maturity, the cucumber roots were rinsed with cold water to stimulate the release of zoospores by Olpidium. Zoospores were then collected by centrifugation. This process was repeated multiple times in order to obtain enough zoospores. DNA and RNA samples generated from the zoospores were then sent to the JGI for whole genome sequencing using the Illumina platform.

Unfortunately, both the DNA and RNA samples turned out to be a mixture of genetic material with various origins, ranging from fungi, plants to bacteria. Back in 2011 when these genome and transcriptome data were generated, bioinformatic tools for binning metagenome data involved with mainly eukaryotic origins were scarce. Thus, the genome and transcriptome data from the precious Olpidium zoospores remained largely untouched until seven years later.

Members of the ZyGoLife Consortium, including Ying Chang standing second from the right. (Courtesy of Ying Chang)

In 2018, as members of the ZyGoLife consortium, my colleagues and I decided to re-visit the Olpidium genome data. Taking the advantage of rapid development of binning methods, we were able to recover Olpidium sequences from the “contaminated” genome data with strong confidence. Taking a conservative approach, we were able to assemble ~75% of the Olpidium genome and retrieve ~300 markers for phylogenetic reconstruction. We were also able to sample extensively among the early diverging terrestrial fungi (i.e., zygomycetes), thanks to the sequencing effort by the JGI and ZyGoLife in recent years. With the much more extensive taxonomic and genetic sampling, our study confirmed the affinity between Olpidium and the non-flagellated terrestrial fungi.

The exact placement of Olpidium, however, didn’t receive unanimous support from different analysis. Most analyses strongly supported Olpidium as the closest relative of the non-flagellated terrestrial fungi but some supported an alternative placement, albeit rather weakly. Further investigation on the source of controversy revealed that the branches among Olpidium and the first few splits in the non-flagellated terrestrial fungi were extremely short, suggesting that there were a series of rapid diversification events when fungi first invaded land.

Intuitively, it makes much sense. Transition to the terrestrial ecosystems exposed fungi to numerous new ecological niches and triggered rapid diversification of the early terrestrial fungal lineages. Our analyses estimate these diversification events occurred approximately 650 million years ago, and that the first terrestrial fungi predate the oldest known fossil record of land plants and evolved in early microbial biocrust environments.

Publication:

- Chang Y et al. Genome-scale phylogenetic analyses confirm Olpidium as the closest living zoosporic fungus to the non-flagellated, terrestrial fungi. Sci Rep. 2021 Feb 5;11(1):3217. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-82607-4.

References:

- James TY et al. Reconstructing the early evolution of Fungi using a six-gene phylogeny. Nature. 2006. 443: 818–822. doi: 10.1038/nature05110

- Sekimoto S et al. A multigene phylogeny of Olpidium and its implications for early fungal evolution. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2011. 11: 331. doi: 1186/1471-2148-11-331

- Olpidium bornovanus on the JGI fungal portal MycoCosm