WALNUT CREEK, CA—Scientists from two-dozen research organizations led by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Joint Genome Institute (JGI) and the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) have decoded genomes of two algal strains, highlighting the genes enabling them to capture carbon and maintain its delicate balance in the oceans. These findings, from a team led by Alexandra Z. Worden of MBARI and published in the April 10 edition of the journal Science, will illuminate cellular processes related to algae-derived biofuels being pursued by DOE scientists.

The study sampled two geographically diverse isolates of the photosynthetic algal genus Micromonas—one from the South Pacific, the other from the English Channel. The analysis identified approximately 10,000 genes in each, compressed into genomes totaling about 22 million nucleotides. “Yet, surprisingly, they are far more diverse than we originally thought,” said Worden. “These two picoeukaryotes, often considered to be the same species, only share about 90 percent of their genes.” To put this in perspective, humans and some primates have about 98 percent genes in common. Worden said that the algae’s divergent gene complement may cause them to access and respond to the environment differently. “This also means that as the environment changes, these different populations will be subject to different effects, and we don’t know whether they will respond in a similar fashion.” She said that their apparently broad physiological range (exemplified by their expansive geographical range) may result in increased resilience as compared to closely related species, enabling them to survive environmental change better than organisms with a narrower geographic range. Testing the hypotheses developed through cataloging their respective inventory of genes, Worden said, will go a long way towards understanding their biology and ecology.

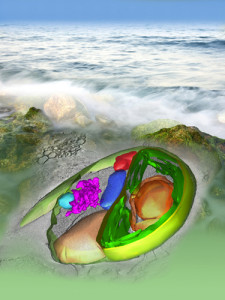

A 3D reconstruction of an electron tomographic slice (0.5 microns thick) of one of the smallest known eukaryotic algae, Micromonas. 3D reconstruction: A.Z. Worden, T. Deerinck, M. Terada, J. Obiyashi and M. Ellisman (MBARI and NCMIR).

Background: Flavio Robles (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory).

Algae were blazing the pathway of photosynthesis long before plants colonized land—so the results bear significantly on terrestrial plant research as well.

“Genome sequencing of Micromonas and the subsequent comparative analysis with other algae previously sequenced by DOE JGI and Genoscope [France], have proven immensely powerful for elucidating the basic ‘toolkit’ of genes integral not only to the effective carbon cycling capabilities of green algae, but to those they have in common with land plants,” said Eddy Rubin, DOE JGI Director.

Tiny Micromonas, less than two microns in diameter, or roughly a 50th of the width of a human hair, are one of the few globally distributed marine algal species, thriving throughout the world’s oceans from the tropics to the poles. They capture CO2, sunlight, water, and nutrients and produce carbohydrates and oxygen. Their productivity—which provides food resources within marine food webs—as well as their knack for capturing carbon, and influencing the carbon flux that may have bearing on climate change, make these algae keen target of study.

“Micromonas is a representative of a well-sampled group of green algae with the largest number of sequenced genomes. With these four genomes in hand–two Micromonas and two Ostreococcus–we can observe patterns of genome organization as well as the diversity between different organisms in this group,” said JGI’s Igor Grigoriev, one of the senior authors of the paper.

Embedded in the genetic code are clues about how photosynthesis transformed from a barren orb into the earth we know today.

“The Micromonas genomes encapsulate features that now appear to have been common to the ancestral algae that initiated the billion-year trajectory that led to the ‘greening’—the rise of land plants—of the planet,” said Worden. As highlighted in the Science article, comparing the strains to each other and in turn to the other characterized algal and plant genomes, will help to illustrate the dynamic nature of evolutionary processes and provide a springboard for unraveling the functional aspects of these and other phytoplankton populations.

Motility is another distinguishing aspect of the ecology of Micromonas. In the relatively viscous saltwater of the ocean, the flagellated Micromonas could give Michael Phelps a run for his money. Unlike other algae genera sequenced to date, these swift swimmers can cut through the water column at a rate of 50 body lengths per second, and are phototactic, meaning that they can swim towards the sunlight from which they derive their energy.

Transmission electron micrograph of one of the smallest known eukaryotic algae, Micromonas.

Credit for TEM: A.Z. Worden, T. Deerinck, M. Terada, J. Obiyashi and M. Ellisman (MBARI and NCMIR).

In previous studies, Worden and her colleagues showed that picoeukaryotes such as Micromonas comprised, on average, only a quarter of the picophytoplankton cells in a Pacific Ocean sampling, but were responsible for three-quarters of the net carbon production. They were also shown to be subject to heavy grazing pressure; their lack of a cell wall may make them more digestible as prey. In this case carbon may be efficiently sequestered by the “biological pump,” the suite of processes that enable the algae to capture atmospheric carbon and transport it from the ocean surface zones to the depths below.

This research serves as a complement to field studies seeking to confirm emerging key players in global carbon fixation. “By understanding which genes a specific strain employs under certain conditions, we gain a view into the factors that influence the success of one group over another,” Worden said. “We may then be able to develop models that could more effectively predict a range of possible future scenarios, that will result from current climate change.” Micromonas may well serve as a bellwether for current and future ocean conditions, helping to guide appropriate decision making, which given the prevailing CO2 trends, is urgently needed.

The genome sequencing of Micromonas was conducted under the auspices of the DOE JGI Community Sequencing Program (CSP), supported by the DOE Office of Science. The CSP was created to provide the scientific community at large with access to high-throughput sequencing for projects selected on the criteria of scientific merit—judged through independent peer review—and relevance to the DOE missions.

The U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute, supported by DOE’s Office of Science, is committed to advancing genomics in support of DOE missions related to clean energy generation and environmental characterization and cleanup. DOE JGI, located in Walnut Creek, Calif., provides integrated high-throughput sequencing and computational analysis that enable systems-based scientific approaches to these challenges.