P. psychrophila genes drive resilience when salinity fluctuates.

The Science

The Arctic microalga Plocamiomonas psychrophila can thrive in changing conditions. A recent study shows that when salinity is reduced in its environment, this alga reveals a remarkable ability to adapt to stress and rapid environmental changes. Researchers were able to identify specific genes that allow the algae to adapt to sudden drops in salt levels, enabling it to take in more nutrients to fuel growth.

The Impact

Over the last 40 years, summer sea ice in the Arctic has decreased by more than 30% in terms of quantity and thickness. Replacing older, thicker ice with younger, thinner ice means more fresh water — and less salt — near the surface where algae grow. Armed with a better understanding of the alga’s stress resistance and ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions, researchers can explore how to better manage the growth, yield and climate resilience of algae — for potential use as biomass or in biomass conversion to biofuel.

Summary

Water temperatures and salinity determine how life thrives in the Arctic, and how different types of microbes form communities. As temperatures fluctuate, salt levels change in the ocean; this affects the growth and survival of the microorganisms that live there.

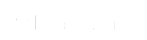

A Communications Biology article highlights how one microalga collected from water on the ice surface handles such fluctuations. P. psychrophila is a species of Pelagophyceae, a microalga shown to thrive in both nutrient-rich and nutrient-poor conditions. It lives in a range of habitats — from brine pockets and melt pools, and within the water column. They are also the primary producers in the marine food web, forming the base of the food chain and providing energy for a slew of marine organisms, as well as contributing to nutrient cycling in these ecosystems.

Researchers studied P. psychrophila’s stress response by comparing how it responded to being moved to a lower-salinity environment with how a control group responded when moved to an environment of comparable salinity.

Researchers collected samples at several points in time to assess nutrient concentration and cell death. Immediately upon transfer, the experimental samples exhibited significant stress with a higher proportion of dead cells recorded. Samples were taken again at two, six, 12 and 24 hours. By the 24-hour mark, these algae showed significant signs of recovery through increased nutrient uptake and decreased cell death.

Scientists then extracted RNA to analyze gene expression, to determine which genes are active under different conditions. This was facilitated in part by RNA library preparation and sequencing from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Joint Genome Institute (JGI), a DOE Office of Science User Facility located at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab). In their analysis, they found the salinity changes led the algae to express genes involved in freezing resistance, adapting to cold temperatures and tolerating the changing salinity of the environment. (The annotated algal genome is available on the JGI’s PhycoCosm data portal.)

This research not only sheds light on the adaptive mechanisms of Arctic microalgae but also opens new avenues for utilizing these organisms in sustainable practices, such as biofuel production and natural fertilizers. By understanding the genetic and metabolic pathways involved in stress responses, scientists can better harness the potential of P. psychrophila.