The work conducted by the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231. This research used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. B.G.P. was supported by the Marine Biological Laboratory, by the National Science Foundation’s XSEDE computing resource (award DEB170007), and through a Challenge Grant from the California NanoSystems Institute at the University of California Santa Barbara. S.C.B. was partially supported by the U.S. Department of Energy under award DE-SC0020173. M.A.O. acknowledges funding support from the National Science Foundation (NSF) (MCB-1553721), the Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Awards Program, and the California NanoSystems Institute (CNSI) Challenge Grant Program, supported by the University of California, Santa Barbara and the University of California, Office of the President. This work was part of the DOE Joint BioEnergy Institute (http://www.jbei.org) supported by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research of the DOE Office of Science through contract DE-AC02–05CH11231 between Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the DOE. R.C. was supported by the Australian Research Council (DP150100244) and the Australian Antarctic Science program (project 4031). The work in the Hallam Lab was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy (DOE) Joint Genome Institute, an Office of Science User Facility, supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231 through the Community Science Program (CSP), the G. Unger Vetlesen and Ambrose Monell Foundations, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Genome British Columbia, Genome Canada, and Compute Canada and the Canada Foundation for Innovation through grants awarded to S.J.H., R.J.G. and T.A.M. acknowledge funding from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, the Beef Cattle Research Council and the Alberta Beef Producers. V.I.R. and S.R.S. acknowledge support for the IsoGenie Project (samples and metadata from Stordalen Mire, Sweden) by the Genomic Science Program of the United States Department of Energy Office of Biological and Environmental Research (DE-SC0004632, DE-SC0010580, DE-SC0016440), and acknowledge the IsoGenie Project Team. S.R., S.C.B., V.I.R., S.R.S. and E.A.E.-F. acknowledge support from the EMERGE Institute (NSF #2022070). Sequencing of the Stordalen Mire samples used herein was performed under BER Support Science Proposal 503530, conducted by the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute, which is supported as described above. This manuscript has been authored by authors at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231 with the U.S. Department of Energy.

Understanding how a fundamental mechanism of evolution allows microbes to adapt to changing environments.

The Science

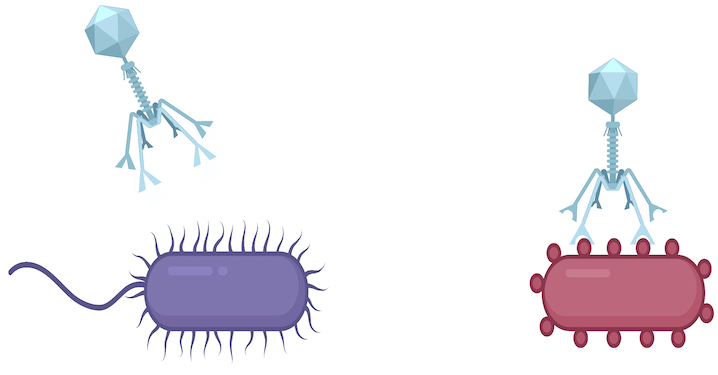

The first step in the deadly dance between a virus and microbial cell is an embrace. For a virus with a “head-tail” morphology, this means using proteins on its tail fibers to latch onto a specific target on the microbial cell’s membrane. Two decades ago, a team discovered a group of viruses that had in their genomes a surprising tool: a “diversity generating retroelement,” or DGR. The DGR could mutate the virus’ tail fiber proteins, and thereby allow them to embrace different cells. Since that discovery, DGRs have been found in other viruses, bacteria, and archaea. But how widely distributed they are, and the roles that they might play in the wild, hasn’t been clear.

Now, to answer these questions, a team led by scientists at the US Department of Energy (DOE) Joint Genome Institute (JGI), a DOE Office of Science user facility located at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), has looked for DGRs in a broad range of publicly available datasets. They’ve discovered that DGRs are not only widespread, but also surprisingly active. In viruses, DGRs appear to generate diversity quickly, allowing these viruses to target new microbial prey.

The Impact

This research provides a much more comprehensive understanding of how a fundamental mechanism of evolution — DGRs — allows microbes to adapt to changing environments. It also sheds light on why the rapid injection of mutations in a particular gene might boost an organism’s fitness. Moreover, the discovery of more than 30,000 DGRs in this analysis, a 20-fold increase over what was previously known, throws open the doors to characterizing how DGRs work at the molecular level. Scientists might then harness them as molecular tools for research and industry applications.

Summary

In their recently published Nature Communications article, the team used publicly available data, approximately half of which was generated by the JGI, to uncover these DGRs. DGRs were found in single microbial and viral genomes, as well as genomes sampled all at once from the same environment, called metagenomes.

Why? Simon Roux, who led the research team and is the head of the Viral Genomics group at the JGI, thinks that if you’re a virus or a microbe with a DGR, you gamble every time you mutate. But, perhaps, it works to keep throwing the dice.

There’s some evidence to support the idea. Study coauthor Stephen Nayfach, a JGI bioinformatics research scientist, found that pieces of viruses with DGRs were found, on average, in double the number of microbial genomes. That means that those viruses accessed many more potential microbial cells or hosts.

This ability isn’t enough to make them super viruses, though, said Roux. There’s a gauntlet of other cell defenses that could prevent viruses from successfully replicating, even if they managed to enter the host cell.

DGRs could prove to be powerful tools not only for viruses and other microbes, but for scientists. One emerging industry application of DGRs is to use them to create collections of protein variants, produced in engineered viruses or microbial cells. Researchers could then use these proteins to recognize individual pathogens and pull them out, like fish on a fishing line, without harming the rest of the microbial community. The study’s publicly available dataset gives researchers the opportunity to study how DGRs work and develop more of them into new biological tools.