How sex chromosomes “older than dinosaurs” could help improve crop yields.

The Science

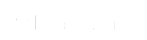

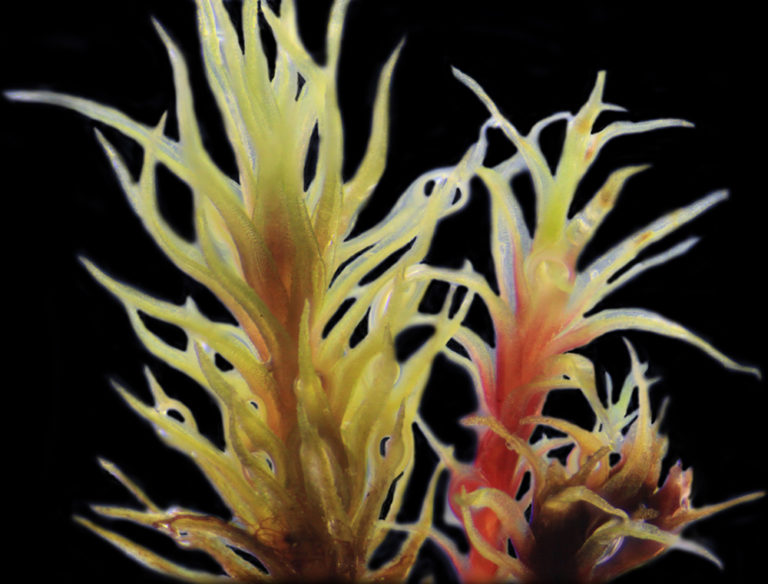

The fire moss Ceratodon purpureus is a short plant with a complex genome. Now, high-quality reference genome sequences of the male and female plants, each representing a single set of chromosomes, are available. The genome assemblies highlight the multiple advances in sequencing technologies applied to the effort.

The Impact

Found on all continents, including Antarctica where it is a major part of the flora, fire moss has adapted to conditions such as UV irradiation, heavy metal contamination, and drought. The moss genomes’ metabolic pathways could lead to the discovery of genes that could be used for multiple biotechnological applications. These applications include crop improvement insights that could benefit candidate biofuel crops.

Summary

On the TV show “Antiques Roadshow,” the guests are often both surprised and pleased to learn the value of their item. Part of that pleasure comes from finally having an answer to the question, “Why bother keeping this?”

For Stuart McDaniel’s lab at the University of Florida, an answer is in sight for a similar question. In a recent Scientific Advances article, a team led by McDaniel and his former graduate student Sarah Carey, now at the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology, reported that high quality genome references are now available for male and female plants of fire moss.

Most notably, the work revealed that the U and V sex chromosomes of fire moss comprise a full third of each moss genome, and are almost four times the size of the next largest chromosome. As the study first author Carey put it, these sex chromosomes first evolved when the Earth’s continents were still Pangea.

McDaniel’s lab continues to work on the enigma of why the ancient moss sex chromosomes continue to evolve so rapidly in gene content and structure. He and JGI Plant Program head Jeremy Schmutz already see how lessons from moss sex chromosomes can be applied to improve crop breeding. For example, Schmutz noted, specific genes of interest could be associated with a plant’s sex. One outcome could be superfemale plants that have increased fruit and seed yield. Conversely, some crops such as bioenergy sorghum may need sterile males; plant breeding experiments could be completed faster without extra crosses.

The work wraps more than a decade of working with researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Joint Genome Institute (JGI), a DOE Office of Science User Facility located at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), and at HudsonAlpha. As the team discussed in a JGI podcast episode about the work, the effort to fully sequence the fire moss genomes ran the gamut of sequencing technologies, from making a bacterial artificial chromosome library to long-read sequencing.

On “Antiques Roadshow,” an item’s appraisal often ends with the owner saying, “We’re not going to sell it, of course.” McDaniel’s lab predicts the decoded complex plant genomes will lead his team to a similar sense of satisfaction.