Analysis reveals the microbial community involved in a bioremediation effort.

The Science

In 1999, the Environmental Protection Agency declared the North Railroad Avenue Plume (NRAP) a Superfund site. The chemical PCE (perchloroethylene) found its way into the groundwater of several communities in New Mexico via leakage from a local dry-cleaner. Researchers identified two bacteria, Dehalococcoides mccartyi and Dehalobacter restrictus, that work together to break down PCE into the chemical compound ethene. Applying genome sequencing and analysis, the researchers identified other bacteria and microbial processes that support PCE biodegradation. The results demonstrate that it takes a (microbial) community to clean up a Superfund site.

The Impact

The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) was enacted by Congress in 1980 for Superfund sites which are hazardous waste areas that require cleanup and long-term monitoring. The DOE has been similarly invested in environmental management, contributing to bioremediation efforts for decades. Identifying resident microbes that can help bioremediate toxic substances has led to the development of cost-effective environmental cleanup strategies.

Summary

In New Mexico, the city of Española, the Santa Clara Pueblo and its nearby rural populations rely heavily on groundwater as their only source of clean drinking water. Over 90% of the PCE in the groundwater has been eliminated at NRAP, and efforts are ongoing to complete cleanup.

The process that was used to clean up the toxic chemicals is commonly known as Enhanced Reductive Dechlorination (ERD.) It is dependent on the presence of the existing microbes in the groundwater and adjusting the environmental conditions to encourage their growth. In this instance, vegetable oil was injected into a specific type of food that was in the contaminated aquifer in 2007 to achieve this goal. In less than four years, parts of the shallow portions of the groundwater were nearly cleared of contamination. By 2020, the water was at contamination levels that are below the minimum amount of what’s allowed in drinking water. However, in the deeper sites, toxic chemicals remain.

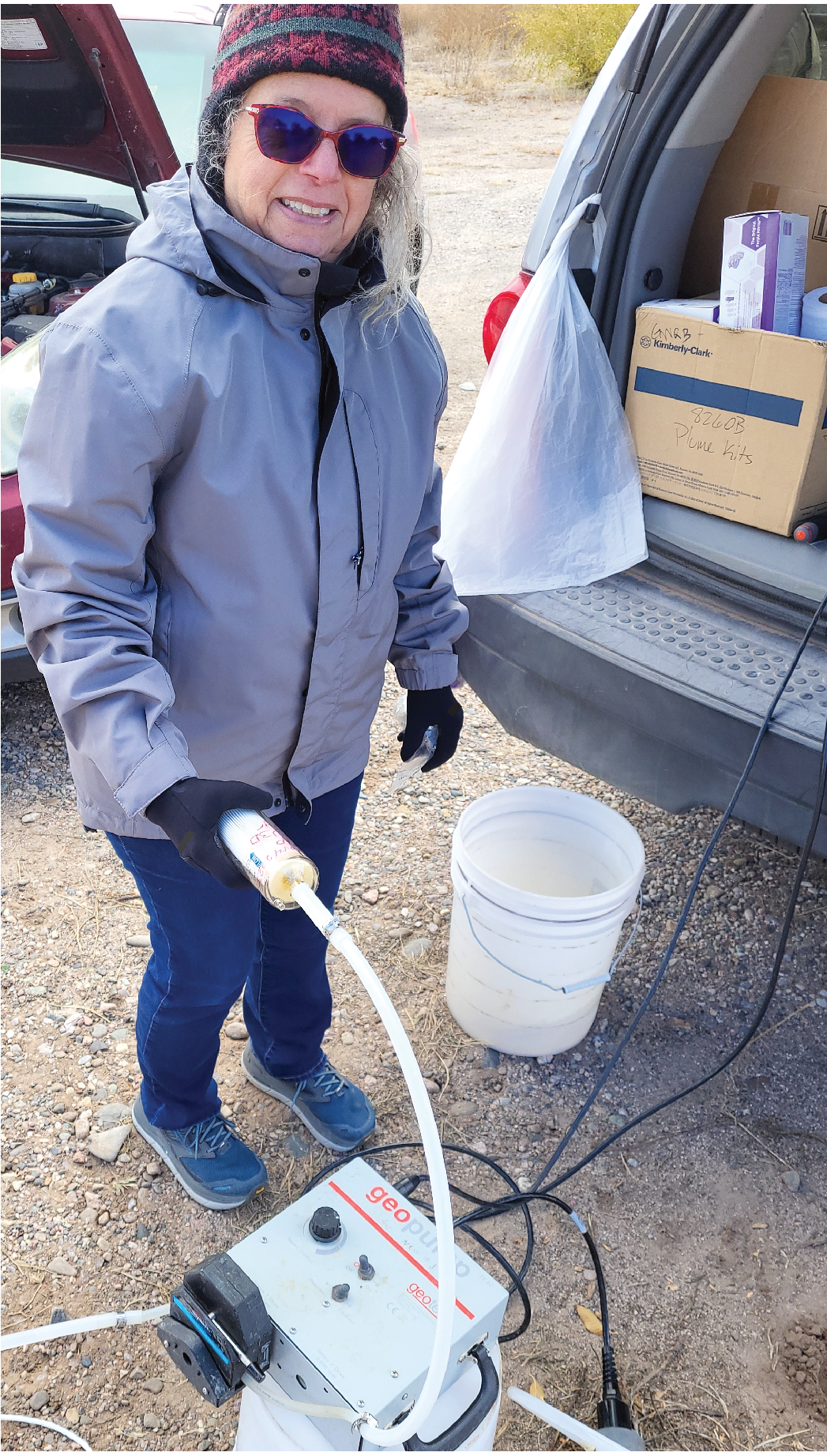

To identify the microbes involved in the early years of the biodegradation process, researchers collected microbial samples from wells at the site in 2007, 2009, and 2010. DNA was extracted from the samples that were sequenced by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Joint Genome Institute (JGI), a DOE Office of Science User Facility located at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and used to identify the microbes involved in successfully biodegrading PCE.

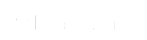

Through the JGI’s Community Science Program, they were able to analyze the resulting metagenomic data. (Data from the project are available on the JGI Genome Portal.) The team has also been able to discover additional microbes that contribute to the cleanup by continuing to access the JGI’s Integrated Microbial Genomes and Microbiomes (IMG/M) system. For example, the team has since identified Dehalogenimonas etheniformans as one of the strains involved in breaking down PCE at the NRAP site. However, the microbial strain’s genome sequence was not in IMG/M when the NRAP samples were originally analyzed a decade ago. The NRAP site is still being monitored and the team plans to continue collecting data to understand the ERD process.