As DOE Office of Science User Facility supported by the Biological and Environmental Research program, we offer deep expertise and a broad toolset.

Video file

We provide access to data and omics technologies at zero cost to researchers.

The JGI at a Glance

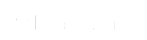

Global Users

Each year, the JGI serves over 2,000 users — researchers with accepted project proposals, at all career stages.

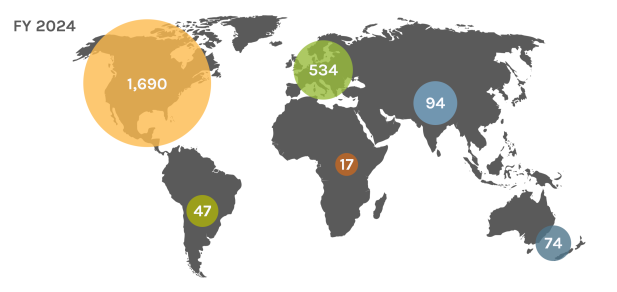

A Diversity of Capabilities

With an accepted proposal, JGI Users gain access to deep expertise and a broad toolset.

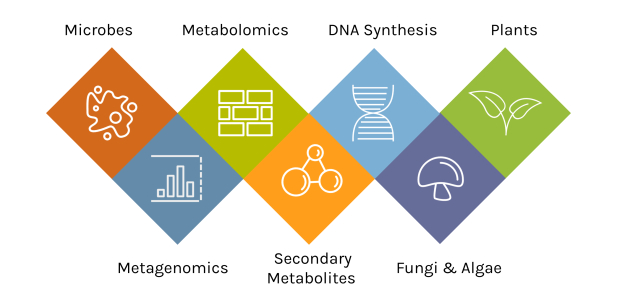

Data Portals

We provide data that supports interdisciplinary work on a broad variety of organisms. Each dot in these networks shows a publication that mentions a given data portal, with work that cross-references multiple portals in between respective hubs.

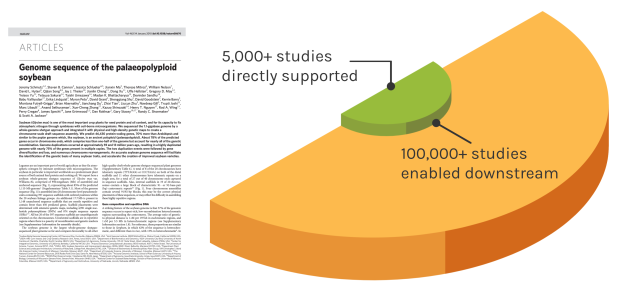

Foundational Work

JGI’s work reverberates over time to enable many discoveries. The Soybean genome shown is one example — since our original reference genome, the entire project has directly impacted over 5,000 unique studies. These works have gone on to influence over 100,000 further studies.

JGI releases latest 5-year strategic plan

“Innovating Genomics to Serve the Changing Planet” lays out how users and the global research community will bridge fundamental knowledge gaps to advance biotechnology and biomanufacturing. This plan aligns our DOE Office of Science user facility with broader national efforts to promote and stimulate a bioeconomy.

JGI announces 2025 New Investigator portfolio

This year, the JGI has accepted novel research projects from a record 30 PIs who have not led previously accepted proposals.

Gotta catch 'em gall

Our Genome Insider podcast follows two researchers studying wasps able to program oak trees to raise their young in structures called galls.